*

The other morning, in a tiny rehearsal room on West 54th Street, an elderly gaggle of legendary dancers got together and formed a rickety pinwheel, which revolved slowly and steadily to a waltz only a Stephen Sondheim could have written.

Carmen De Lavallade was, by turns, choreographing and participating in this charming twirl. The Tiger Lily of yesteryear, diminutive Sondra Lee, was making all the right Jerome Robbins-trained moves. William Duell was bearing the same audience-winning grin which he has had since 1776 (the musical). And Frederic Franklin was showing grace that belied his 96 years.

The music that moved and animated them was called "The First Dance." Though unmistakably Sondheim, it's also rather unidentifiable, coming from his long-"lost" score — the one (and the only one) he ever did for TV: "Evening Primrose," and this is not one of its four songs which cabaret stars smuggled into the mainstream.

This 50-minute made-for-television chamber musical aired just once — Nov. 16, 1966 — as part of the "ABC Stage 67" television series, but somehow, over the years, it has become the most-requested video in The Paley Center for Media's collection. Anthony Perkins starred as a stressed-out poet who opts to hide from the hectic hurly-burly of real life — in a department store, where he has peace and quiet and every creature-comfort at his fingertips. Unfortunately, after hours, he discovers among the mannequins a secret society of hermits who had the same idea — first.

Led by Mrs. Monday (Dorothy Stickney) and Roscoe Potts (Larry Gates), they live in constant fear of discovery by the night watchman or that one of their number will bolt back to the real world. To prevent this, there are The Dark Men, enforcers at the Journey's End mortuary, who turn turncoats and burglars alike into mannequins — and turn "Evening Primrose" into a bargain-basement Brigadoon.

Fresh from "Sixteen Going On Seventeen" in the movie of "The Sound of Music," Charmian Carr was Mrs. Monday's 19-year-old handmaiden, who falls for new-arrival Perkins and plots an escape with him back to the real world. The story ends, less merrily than most musicals, pretty close to a "Twilight Zone" episode.

Sondheim always liked the show in this form. "What I wanted to do was find ways of using television," he has said, "write a musical that could not be done on stage."

Nevertheless, a stage version had a three-week run in London five years ago (it was one of Betsy Blair's last appearances), and the U.S. premiere, directed by Tony Walton, will occur (in a staged concert) Oct. 25 at the Gerald W. Lynch Theatre at John Jay College.

| |

|

|

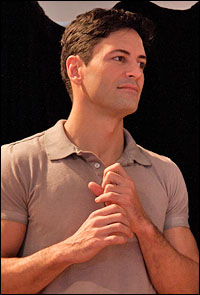

| Sean Palmer in rehearsal for the new concert. | ||

| photo by Krissie Fullerton |

The day after the Manhattan concert, Oct. 26, Entertainment One and the Archive of American Television will release, for the first time on any format, an extras-laden black-and-white DVD of the telecast, digitally re-stored and re-mastered to exacting standards.

On DVD, the Paley Center's intrepid "detective"-in-residence, Jane Klain, conducts an audio interview with Carr, whose entire showbiz career consisted of two roles — yet both of them embraced the top tunesmiths of her day (Liesl in Rodgers and Hammerstein's "The Sound of Music," and Ella Hawkins in this Sondheim musical).

Her second career was interior decorating, and her clients included a huge "Evening Primrose" fan, Michael Jackson, who wanted his bedroom done up in mannequins.

The television show was helmed by veteran director Paul Bogart, who, 91 next month (Nov. 21), looks back on the whole experience with much-justified pride — and this, from a man who won his five Emmy Awards for nonmusicals ("The Defenders," "All in the Family," "The Golden Girls" and two "CBS Playhouse" presentations).

"I wouldn't change that experience for anything in the world," he beamed proudly over the phone recently from his home outside Chapel Hill, NC. "I'm proudest of letting the music happen. I just tried not to get in the way. Sondheim is no patsy, y'know. You can't put him in a slot. You take a song like 'I Remember [Sky],' with its beautiful, gentle tones, and then you contrast it with 'Take Me to the World,' which is a very old-fashioned duet of the old musical-theatre school in which the hero and the heroine sing about their future together and they soar higher and higher until they burst into the stratosphere. It's very Rudolf Friml."

With "I Remember," a song Sondheim supposedly wrote overnight, "I didn't want to watch him watching her," so Bogart dollied past Perkins to a closeup of Carr singing, removing all Jeanette MacDonald-Nelson Eddy allusions.

Bogart admitted he was less satisfied with "When," in which the young lovers sing their thoughts while the store people play bridge. "It was always conceived as a voiceover song, but I didn't like being on their faces while they were thinking. I didn't like that they had to make faces. An actor is high and dry when he has to act to his recorded voice. I'd do that differently now. I'd have them sing just outright, and the other actors would just not hear 'em. On Broadway, you can get away with that." The opening number, "If You Can Find Me, I'm Here," which Perkins sings when he is safely ensconced inside the department store, got an elaborate production inside the now-defunct Stern Brothers department store across from Bryant Park. (Macy's was originally to be used, but executives rescinded the invite, fearing a nest of hermits living it up on the premises would reflect badly on its security system.)

That song ended with repeated blasts of "I'm Here," only one note off from the finish of Sondheim's "I'm Still Here," which was incubating at the time. Sondheim and Goldman had hit a creative wall after a year's work on a show called The Girls Upstairs (later redubbed Follies, which would produce "I'm Still Here"), and funds were needed for Goldman's enlarging family so Sondheim prevailed on ABC exec Hubbell Robinson (who was married to a friend of his mother's, Broadway star Vivienne Segal) to commission an original hour musical for Goldman's rent. They picked "Evening Primrose," even though the network didn't care for that title or for Sondheim's alternative (A Little Night Music).

If Perkins looks vaguely cross-eyed during the first song, put the blame on Sondheim, who readily accepts it. He told the actor to look around the edges of the camera rather than directly at it. Nevertheless, Perkins blamed the director for it.

"Tony was a real movie actor and had no problem at all with the lip-synching," Bogart recalled. "He was very fixed about what he was doing and did it well."

The producer was the prestigious John Houseman, before he turned into a late-blooming actor. "I'd never worked with him before, but I did subsequently when he was acting. He was in 'The Adams Chronicles,' playing some dignified statesman whom I can't remember [Justice Gridley]. I loved him. He was a dear, sweet man." A bit on the sour side was scripter Goldman, who was very protective of his prose. "He wouldn't let anything be changed, not even a word. He just drove Tony up the wall. When Tony asked for changes, he declined. I felt that Jim Goldman was cold to me. I usually have a lot to say to authors, but not this time. He kept himself apart."

Sondheim, in contrast, was something of a sun god on the set, radiating warmth and enthusiasm. "He brought great, positive good cheer with him. He was happy to be there and happy that it was being done, and he projected nothing but happiness.

"It was many years later that I saw his steel — at the opening of Merrily We Roll Along. I remember I said something he didn't like, and he snapped at me. But for Primrose, he was splendid. He couldn't have been nicer. I was in awe of him.

"The most stressful part of the shoot was the finish of it," he shivered, remembering. "There was a bunch of retakes of the last shot because of an actor's blink, and the studio had been leased to another show, which wanted to move in, and we were sitting there so there was a good deal of argument and screaming. It was awful, still not having enough material shot and doggedly going on while people were yelling."

Even now, 44 years later, Bogart would love to get another shot at it. "In fact, I'd like to do it all over again, the whole thing. Oh-ho, yeah. With all the possible computer graphics available, you wouldn't have to make people stand still and play dead. You could make it happen. And the effects would be more ghostly. These people were a lot stranger and other-worldly. You can do things now that you couldn't do then."